|

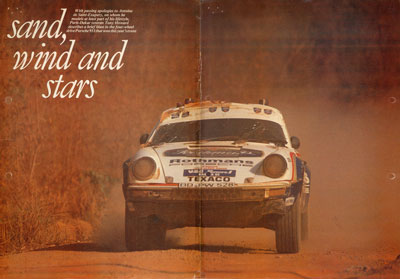

With passing apologies to Antoine de Sainte-Exupery, on whom he models at least part of his lifestyle, Paris-Dakar veteran Tony Howard describes a brief blast in the four-wheel drive Porsche 911 that won this year’s event. DURING a hectic fortnight that took in two grands prix, a trip to the Scottish Highlands in glorious weather, dubbing TV commentary on the East African Safari, an earthquake and visits to Pompeii and the spectacular Monte Cassino monastery, the most vivid occasion of all was a spell behind the wheel of a Paris-Dakar four-wheel-drive Porsche 911. The British are slowly getting the message about this predominantly French "rallye raid", arguably the most challenging annual event of the international motor sporting calendar. Yet, even after driving in it three times and trying to spread the word, I am met with incredulity when I attempt to explain it and near-disbelief when I merrily say I want to do it again.

"We've voted that you get nine out of ten for spectacle, if nothing else. That really turned you on, didn't it?" "Yeah, yeah." "You're already wondering how you can get your hands on one of these cars for next year." "Oh, yeah." Then, glancing impishly at Helen Jordan from Rothmans: "Even as we speak, you're hatching an evil plot to pull in the readies from a sponsor." "Right on." With memories of the desert still clear, the performance of the 911s seemed all the more remarkable. For the Rallye Paris-Dakar has destroyed much rugged machinery as well as being the downfall of many a strong man.

After a 20-day struggle, covering more than 6,000 miles of some of the world's most inhospitable terrain, less than 40 of the 200 cars that start can be expected to be classified as finishers. Other crews will have abandoned smouldering debris or given up in fatigued despair, stuck fast in cloying sand with smashed transmissions or axles bent beyond repair. In many cases, I am convinced, a crew's morale simply collapses in face of a relentless onslaught from bitter cold in the desert night, searing daytime temperatures, the empty loneliness of vast Saharan wastes, gut-churning crunches from rock to rock or the remorseless grind through endless miles of deep sand. All this can be so overwhelming that it brings crews near to tears. They lose their grip on their will power. What would otherwise be a relatively easy mechanical problem to overcome suddenly becomes too much for shattered remains of ingenuity and determination.. It was no over-statement when the French satirical newspaper, Le Canard Enchainé, dubbed the event "Le rallye des masos.." When Paris-Dakar is good, it's very good, but, when it's bad, it's horrid.

There can be few experiences as satisfying as blasting for eight to 15 hours across rolling expanses of open desert, keeping it all together, moving up maybe 10 or 15 places, and finding your way spot-on to a pin-prick on the map that represents a lonely oasis chosen for the night's bivouac. Better still, in a way, after slaving to put something right in the heat of the day, is then to pick your way across vast tracts of black nothingness, guided only by stars and a crazily spinning compass, pick up wisps of dust from other competitors, and arrive at a control just five minutes within your maximum allowed time. Self reliance is absolutely essential if you want to play this game, for the desert is no respecter of persons. If you break something on the car, you had better be prepared to take a stab at bodging a repair because, no matter how well you are supported, your back-up crew must follow the same route and could be hours behind. That’s how it was for Jacky Ickx in the 1984 Rallye Paris-Dakar when, once again, he set out to tackle this "incalculable adventure".

Rothmans had the money available. Porsche was well advanced with development of a Group B four-wheel-drive version of the Carrera for World Championship rallies of the more ordinary kind. Before the Audi Quattro emerged as a dominant force in rallying, its major mechanical units had undergone a baptism of fire when Freddy Kottulinsky won Paris-Dakar with a Volkswagen Iltis in 1980. Ickx had won the 1983 event with a Mercedes Benz G-wagen. The "kit car" specification that Porsche came up with draws on the Group B work as well as standard production parts straight out of the stores. Ride height is raised to give ground clearance of more than 10 inches. Steering and torsion bars are standard, though stiffer front and rear anti-roll bars are employed. Front suspension is from the Group B car, with two wishbones and two Bilstein dampers on each side. At the rear, there are 911 Turbo trailing arms, clad in plastic to minimise stone damage. To the single dampers, coil helper springs are added, and the drive shafts are drilled out to reduce weight. The discs are standard Carrera components except that they too are drilled (laterally) for lightness.

Further use of off-the-shelf components is made in the four-wheel-drive transmission. Urge to the front wheels is fed via a 944 prop-shaft and 924 Turbo trans-axle. Between these elements and the five-speed gearbox at the rear is an epicyclic torque splitter giving 30:70 distribution front to rear, but capable of being locked to give a 50:50 split. The differential in the rear trans-axle is locked, but the front one is free. A bog-standard Carrera flat-six engine with normal aspiration is used. The only real concession to the low-grade petrol obtainable in parts of West Africa is a marginal reduction in compression ratio, and output is relatively modes for Porsche – "only" 225bhp at 5,800rpm, though maximum revs are 6,800. It says much for the electronic fuel injection and ignition that none of the drivers felt it necessary to use manual over-rides of mixture or timing. Overall fuel consumption for the event is calculated at 15˝ mpg, quite remarkable in view of the fact that the car is being driven hard all the time – either flat-out or churning through soft going. Nevertheless, Paris-Dakar demands that a car really does have to be capable of around 500 miles at competitive speeds before re-fuelling. Filling stations are rare, and seldom have electricity. Often, fuel is brought out into the middle of the desert in large tankers that rendezvous with competitors.

Fifty nine gallons of petrol weighs about 420 lbs, equivalent to two extra crew members, and the less you have to carry, the quicker you'll be able to run without destroying the car. Balancing the draw-off from each of these big tanks is important too, so as to keep the car trimmed correctly. The aim is to adjust it so that, after a jump, the car will land slightly tail down, rather than diving head first into a hole. Though virtually standard in appearance, the bodywork is extensively changed. Under the skin, engine and damper mounts are re-inforced, and a transmission tunnel is fitted. The front end is restructured to accommodate the altered suspension. Front wings are made of GRP and carbon fibre, saving 44 lbs overall, while GRP is also used for the front boot lid, doors, engine cover and rear spoiler, and side windows are Plexiglass. The underside is protected by a Kevlar/carbon fibre shield almost half an inch thick. A full roll cage surrounds the crew, and they are accommodated in Recaro seats with full harnesses.

All up, with full fuel tanks, the Paris-Dakar Porsche weighs in at more than 3,100 lbs. Thanks to the big footprint of the special Dunlop 205/15 tyres, sand mats are not required to aid traction on steep or heavy going. Three such cars were entered for the 1984 event. Ickx, looking for a second win in a row, shared one with French actor Claude Brasseur, his co-driver in 1982. René Metge, French saloon racing champion and 1981 Paris-Dakar winner, said, after being disqualified in 1983, that he would never touch the event again. But there he was once more, with Dominique Lemoyne in the second car. The third was crewed by Roland Kussmaul, manager of the project, and his fellow technician from Weissach, Erich Lerner. One thing you can be almost certain of on Paris-Dakar is that, if you think you have all the answers in the preparation of the car, there will be something new and unexpected to go wrong. This happened to Ickx en route for Tamanrasset, 4,500 ft up in the mountains of southern Algeria. A stone penetrated the wiring, and caused a short circuit that melted virtually the whole loom. As a result, the car fell to 139th position. But, meanwhile, Metge was third, and Kussmaul was 15th after stopping to help Ickx.

However, once he had got his car going again, Ickx displayed all his usual pace, and climbed quickly back up the field. Though he had too great a backlog to overcome, and had to settle for sixth place overall, a little less than six hours behind Metge. Kussmaul, after rolling twice, was classified 26th and good enough to help take the team prize. That one member of a team should roll twice and another should have his wiring burn out is really no big deal to Paris-Dakar veterans. What is remarkable in the context of an event of this magnitude is how little other trouble the team claims to have experienced. The Dunlop tyres took 5,000 miles to wear out, and, between them, the three cars suffered only five punctures between start and finish. Believe me, that is a record to be envied. Drive shaft gaiters had to be replaced a number of times on all three Porsches, but Metge's car required only one damper to be substituted. Brake pads lasted 4,500 miles, and the discs lasted the full distance. The engines went all the way without an oil change, and only five litres were put into Metge's car. It all seems too good to be true. However, the results speak volumes, and there was the hardware, in the form of the Kussmaul car, to drive on the "Munich desert" undulating, rough, dusty and well chewed up by tanks. Accustomed as I am to the more elegant and spacious interior of a Range Rover desert racer with its high driver's seat and good view, first impression of the Porsche was that it was pretty crowded inside and that the view across the dunes might be limited.

That done, and trussed like a turkey into the wrap-around seat, the first step is to align your feet properly with those offset pedals. Wise move. The gear-change is clunky, but first is easy enough to find. The racing clutch takes up the drive undramatically, and allows the car to be trickled away from a standstill. Little things like that help when you are doing your number in front of Porsche competitions chief Peter Falk for the first time. But, when you press that pedal on the right, it's all there. With that inimitable shrieking growl, the engine immediately gets into its stride, the revs zap upwards, and you hurtle off into the wide blue yonder. Clunk, and you have successfully negotiated second gear – not bad going for a first try when things are happening so rapidly. Another clunk, and you have ... yes, it is third. Already, you can tell why this is a great device for a Paris-Dakar. The engine seems so flexible, and has lots of grunt. Suspension is firmly damped, making the car stable even in tricky off-balance situations. Yet landing after each jump is mopped up so well that you don't think: "Hell, next time that happens, the thing will fly into a million pieces."

Rather sensibly perhaps, since there was less than an hour to get the hang of the car, the area chosen did not present the opportunity to exploit the top gear performance. However, there was enough straight to wind it up to 5,500 in. fourth if you gritted your teeth and left the braking late. Arguably, any clown can drive at full bore in a straight line. Getting round corners really quickly can be quite another matter. In this car, it would take a while to master the technique. The problem for the newcomer is that rear wheel grip is so good that it is quite difficult to break traction and kick the tail out. To do this, you need to arrive at a corner fast and have room to induce a pendulum effect, flicking first one way and then the other to create an acute angle with the apex. If you arrive slow, then try to boot it round, the tendency is for the front end to plough ahead. This is obviously where optimum fuel trim can be helpful in maintaining front wheel adhesion relative to the rear. Nevertheless, I couldn't help feeling that it would only take a couple of days in the desert to get in the groove with the car. There's nothing like a good long charge of adrenalin to overcome the inhibitions that otherwise prevent you from getting anywhere near such a car's potential. If anyone's offering, I've set aside next January for a winter break in the desert ... Copyright © 2010 by Anthony Howard for Fast Lane. All rights reserved. |