|

very much alive

Sam Cody, showman and aviation pioneer Farnborough has seen it all and now enjoys a new era... FARNBOROUGH is the gateway through which Britain entered the aviation age. Close to Aldershot, “home of the British army”, it saw the establishment of HM Balloon Factory in 1908 to provide artillery regiments with more effective spotting. This establishment was renamed the Royal Aircraft Factory in 1911, and generated a number of designs, some of which went into series production during World War I. Among the talent developed during this period were Geoffrey de Havilland, who later founded his own company and created the first jet airliner, the Comet, and Henry Folland, later chief designer at Gloster Aircraft Company and founder of Folland Aircraft. To avoid confusion once the Royal Air Force was established in 1918, Farnborough was renamed the Royal Aircraft Establishment, and remained as such until 1988, when it was redesignated as the Royal Aerospace Establishment to keep up with the times.

The RAE was so central to aeronautical development that during World War II, it is thought, Hitler avoided bombing the site in the hope of using it for further research once England was occupied. Countless initiatives from the RAE have spurred the progress of aviation worldwide, and Farnborough’s record includes the first UK flight by a jet aircraft and fatigue-testing on the Concorde prototype during the 1960s. More mature readers may recall the first public appearances of the “flying bedstead”, precursor of the Harrier jump-jet, and many other innovations at the Farnborough Air Show, which opened to the public to in 1949. It soon became a national institution, making hearts beat faster with demonstrations of Britain’s civil and military aeronautical prowess. It continued as an annual national morale booster until 1962 when it became a biennial international event, hosting exhibitors from all over the world, and nowadays it alternates with the Paris Air Show. The 2006 Farnborough Air Show attracted 42 official delegations from around the world, 1,360 commercial and other exhibitors and 243,000 visitors. It was credit with generating $21 billion of aviation orders, and contributed more than £17 million to the local economy. After a 50-acre site on the south side of the airfield was put out for commercial tender, Carroll Aircraft established a civil area1989, but its holding company went bust in 1995. Once the Ministry of Defence concluded the 600-acre Farnborough airfield was surplus to requirements, the site was sold to TAG on a long lease in 1997, with the proviso that it was to be used only for business aviation and the Air Show. TAG’s aim has been to preserve Farnborough's history and also to establish it as Europe's Number 1 all-business airport. Improvements embrace resurfacing the runway, installing new ILS/DME - instrument land system and distance measuring equipment, new lighting and signage, and many other safety and environmental upgrades. Significant though these are, they do not match the visual impact Farnborough's award-winning imaginative new buildings, designed by Reid Architecture to form a unified business aviation "campus”. This embraces a very striking control tower, triple hangar, and completely refurbished engineering installations.

The construction programme culminated in May last year when the Duke of York opened the impressive executive terminal building. Costing £10.2 million, this 54,000 sq ft facility provides ground services for business aircraft, and is also TAG Farnborough’s operational HQ. It features a cafe and conference facilities for passengers and pilots. Most airports have to watch their Ps and Qs in relation to nearby residential communities. Farnborough’s operating hours are restricted to 7am-10pm on weekdays and 8am-8pm at weekends, and weekend movements are strictly limited. Overall, there is a cap of 28,000 take-offs and landings a year. However, the problem may not be as serious as it at first seems, Farnborough’s CEO Brandon O’Reilly points out that it devoted to business flying. He says: "There are very few dedicated business aviation airports – there are commercial airports such as Luton and Stansted, and then there are smaller airports which also deal in general aviation such as flying clubs, etc. But the facilities at Farnborough are absolutely dedicated to business aviation – there's nothing else like it, certainly in Europe. "Only 10-20 per cent of our customers come through the terminal – we have around 50 flights taking off per day, with the average number of passengers per flight being around two people. So that's 100 outbound passengers, of which only 20 or so will use the terminal.” Farnborough is also the base for Flight Safety International’s European training centre, representing a major investment by FSI, and its largest pilot training school outside the USA. Opened in 2005, the 92,000 sq ft facility houses 15 full flight simulators for business jets, regional aircraft and helicopters, as well as interactive classrooms, high-tech training devices and pilot briefing rooms. A 180-room four-star hotel is due for completion at London Farnborough Airport in mid-2008. It is hoped it will find favour with passengers, crews, pilots attending Flight Safety courses and the local business community. Also part of the TAG group – with the McLaren Formula 1 team, TAG Farnborough and TAG Aeronautics – TAG Aviation is currently the world’s largest operator of charter executive aircraft. It owns, manages and operates nearly 200 aircraft, which have flown more than 17,000 hours in the past 12 months l

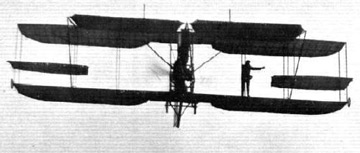

First heavier than air flight in Britain... A MAJOR player in the rapidly unfolding early drama of Farnborough was Samuel Franklin Cody. Not to be confused with Buffalo Bill Cody, Samuel was a flamboyant American showman, born in Iowa in 1867. It is said that in his youth he was a cowboy, learning how to ride and train horses, use a lasso, shoot and hunt buffalo. And later he joined the Alaskan gold rush as a prospector. From these experiences, he developed his Wild West show, in which he starred as “Captain Cody, King of the Cowboys”. First he toured the US, and then crossed the Atlantic to entrance audiences with his demonstrations of horsemanship and rifle and pistol sharp shooting. Cody developed an interest in kites, using finance from his shows to develop ever larger devices to fly higher and higher. In 1901, he patented a winged version of a double-cell box kite, which was demonstrated several times at up to 2,000 ft. Cody offered the kite to the War Office for use in spotting during the second Boer War. Basing it on his kite ideas, Cody built a glider, and flew it several times in 1905, but it was not repaired after a heavy landing.

When Cody crossed the English Channel in a canoe towed by one of his kites, the Admiralty realised the potential of kites as observation platforms. As a consequence, he flew a kite from the battleship HMS Revenge in 1908. He was a busy man. For in 1907, the army had agreed to fund development of what was essentially a motorised kite, designated British Army Aeroplane No.1. He began testing the device in September, 1908, progressing through a series of gradually longer hops until he attained 1,390 ft and crashed at Farnborough on October 16 – the first heavier-than-air flight in Britain. At this juncture, the War Office declared there was no future in the idea and terminated Cody’s contract. One of those great egg-on-face moments of history. Cody soldiered on, however, repairing the aircraft and continuing flights. In 1909, he received Royal Aero Club certificate Number 9, flew passengers for the first time in the world, and made a world-record cross-country flight of 1 hour 3 minutes. He raised the game in 1910, when a flight of 4 hours 47 minutes in a newly aircraft won him the prestigious Michelin Cup. A float plane was another of his innovations, but it broke up at 500 ft, killing Cody and his passenger, in 1913. Cody was buried with full military honours in Aldershot, where an estimated 100,000 turned out to bid him farewell l

1428 words Copyright © 2007 by Anthony Howard: editor, Mediaplanet private aviation supplement with The Times (16 tabloid pages) |