|

Keith Duckworth Multi-talented, super-confident, deep-thinking

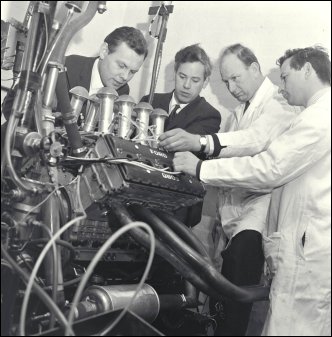

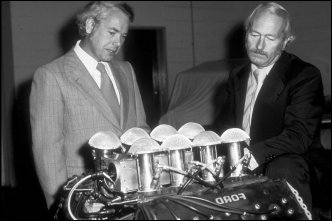

THANKS to his deep insights, huge concentration, stamina and good fortune in being in the right place at the right time, Keith Duckworth became a true maker of champions and one of the most significant influences on world-wide motor sport in the 20th Century. To quote John Blunsden's introduction to his fine book The Power To Win (Motor Racing Publications, 1983): "The decision of a large multinational corporation to back the entrepreneurial flair of a brilliant young designer and his talented team of engineers was to bring each of them considerable rewards. "But the chief beneficiaries of their long-lasting association have been the ever-increasing number of people for whom motor racing has been their livelihood and the countless thousands of spectators for whom the sight of battle between professionally run teams of well-matched cars and drivers continues to be of such absorbing interest. "They should all be grateful for that day when Ford and Cosworth sat down together and decided to 'do an engine'." The legend remained undimmed when, 23 years later, Duckworth died last December after a short illness at the young age of 72. Indeed, though Formula 1 progress made it inevitable that the DFV could not remain the prime engine indefinitely, such is its enduring popularity in the historic racing world that Cosworth resumed manufacture in 2004. The plaudits to Duckworth are legion, and it would be curmudgeonly not to be bucked by descriptions of oneself such as "admired for not accepting what you are told is fact, and taught all those close to him to think". Or: "multi-talented, super-confident, deep-thinking, forthright, stubborn, often combative, dismissive of fools, gregarious in company, but dangerous in argument - a one-off in every respect". Metaphorically, if not literally, it was with these qualities "strapped to their backs" that over the decades innumerable household names were able to express their talents in their drives for fame and fortune, most notably in Formula 1 and America's CART and IndyCar racing. That flawed genius Colin Chapman, whose Lotus cars ran rings around so many august rivals for so many seasons, played a pivotal role in the story. For it was Chapman who early on employed Duckworth and Mike Costin, his lifelong friend and partner in establishing Cosworth Engineering, itself destined to become legend and a moniker much sought after by anyone with the imagination to see a car as more than mere traffic jam fodder. Duckworth soon struck out from Lotus on his own, while Costin remained contracted to Chapman for rather longer. A key event in the trio's stellar fortunes was the authorities' decision to abandon the 1½-litre Formula 1, itself the successor to the 2½-litre F1, and replace it with a 3-litre limit from 1966. There were dark mutterings about wily Continental conspiracies to thwart English garagistes, among them Chapman developing a penchant for trouncing the grandes marques with his cheeky, nimble chassis designs. Certainly, Chapman viewed his imminent power unit options as less than tantalising. So he began lobbying. He addressed the great and the good at Britain's Society of Motor Manufacturers & Traders, probing the possibilities of some sort of national, or even government resourced, engine programme. This might have been a goer under Herr Hitler or Signor Mussolini but didn't really have prayer in laissez-faire Britain. More to the point, Chapman had already established a friendship with Walter Hayes, a national newspaper editor recruited to head Ford's PR in Britain. Hayes had the imagination to comprehend the potential in Chapman's vision and the guile to shepherd the project through the multi-national corporate minefield. The upshot was that, in mid-1966 with a £100,000 contract from Ford in his pocket, Duckworth began drawing his designs for a 3-litre V8 with twin overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder, destined for acclaim as the Ford Cosworth DFV - double four valve. The contract stipulated provision of five engines for the following racing season. Duckworth became a hermit for nine months, focusing intently on his brainchild for 16 hours a day away from the distractions of his office, and losing 40 lbs in the process. Little did anyone dream - including Duckworth, Chapman, Hayes and Henry Ford II - where this enterprise would lead. The reality has echoed some fantasy of derring-do from the Boy's Own paper. Chapman's Lotus 49, sporting a DFV not only as propulsion but also bolted to the cockpit and forming the car's rear chassis, made its debut at the 1967 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. It certainly hit the headlines as Jim Clark romped off around the sand dunes, scoring a first-outing victory for car and engine. Clark proved this was no mere flash in the pan by also winning in Britain, the United States and Mexico. After Clark's death in a Formula 2 race at Hockenheim in early 1968, it fell to Graham Hill to win that year's drivers' championship with the DFV-powered Lotus, which took the manufacturers' title. And wider availability of the DFV also brought wins for the Matra and McLaren teams. Cosworth went on to power a long list of driver and manufacturer championship wins, making it the most successful engine manufacturer in the history of Formula 1. The company replicated these triumphs in a variety of other arenas such as IndyCar, Champ Car and sports car racing, as well as rallying and motorcycling. Continuous development of the DFV over 16 years saw its power increased from an initial 405 bhp at 9,000 r/min to 510 bhp at 11,200 r/min, and its weight reduced from 365 lb to 340 lb. Hill's fellow beneficiaries of the DFV came to include Jackie Stewart, Jochen Rindt, Emerson Fittipaldi, James Hunt, Mario Andretti, Nelson Piquet, Alan Jones and Keke Rosberg. Ultimately, the DFV's tally amounted to 12 drivers' titles, 10 manufacturers' championships and 155 race wins during its 15-year reign. A parallel saga began across the Atlantic with the introduction in 1975 of the DFX, an alcohol-fuelled turbo-charged derivative of the DFV that generated 720 bhp at 11,000 r/min. This became the weapon of choice among the Championship Auto Racing Teams and IndyCar fraternities, winning 151 races including 10 Indianapolis 500s between 1976 and 1989. Among those who owed their titles to the DFX were Rick Mears, Johnny Rutherford, Mario Andretti, Al Unser and Bobby Rahal. Wanting a share of Ford's near monopoly of glory in an increasingly competitive automotive world, other major manufacturers essayed Formula 1, among them Porsche, Renault, Honda, BMW, Mercedes-Benz and more recently Toyota. As Renault ventured onto the scene with its innovative turbo-charged engines in 1977, there were knowing smiles as clouds of white smoke all too frequently presaged the retirement of the team's cars. But soon the French cars were winning races and the turbo era was well under way. This gave rise to Cosworth's own 1,000 bhp 1½-litre turbo V6 as the DFV's dominance began to be eroded. To calm things down, turbo 'hand grenade' engines were abolished from 1989 and replaced by a 3½-litre naturally aspirated formula. Cosworth responded with the HB V8 that won 11 grands prix between 1989 and 1993. The HB also powered the Jaguar XJR14s that scooped the 1991 World Sports Car Championship. The momentum continued as Nigel Mansell won the CART/Indy title with the XB engine in 1993, and Jacques Villeneuve followed suit in 1995. As Michael Schumacher began his meteoric rise with the Benetton team, he took his first title with the Ford Cosworth Zetech V8 in 1994. Jackie Stewart's 'stairway of talent' led to the establishment of Stewart Grand Prix, racing with Ford Cosworth power from 1997. In 1998 Ford acquired Cosworth Racing as the prelude to the new CR-1 engine, supplied to Stewart for 1999. By mid season Ford had bought out Stewart, and later announced the team would compete as Jaguar Racing from 2000. However, caught in the vortex of corporate politics, the venture was not a success, and the outfit was sold to Red Bull at the end of 2004. Let Keith Duckworth have the last word: "We thought it must be possible to make an interesting living messing about with racing cars and engines. That was the total objective behind the formation of Cosworth." Not a bad result from a simple objective l Anthony Howard

Copyright © by Anthony Howard for Vehicle Engineer Pictures: Ford media library |