|

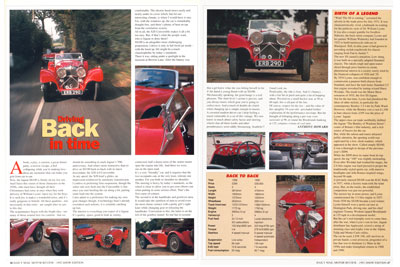

book, a play, a cartoon, a great dinner party, a narrow escape, a bed collapsing while you’re making love - such memories make one grin from ear to ear. Now, the Jaguar SS 100 is firmly on my “grin list” too. And I have this vision of those characters in the 1930s, who must have thought all their Christmases had come at once when they took delivery of William Lyons’s latest toy for the boys. It is such fun, it makes a wonderful noise, and it is really gorgeous to behold. All these qualities – though not necessarily in that order - are prized in cars to this day. The acquaintance began with the bright idea - too many of those around here for comfort - that we should do something to mark Jaguar’s 70th anniversary. And what could be more instructive than to drive an SS100 back-to-back with its latest descendant, the XJS 4.0 Convertible. At any speed, the XJS kind’a glides, an impression reinforced by automatic transmission. I confess to preferring firm suspension, though the softer ride now built into the Convertible is fine once you start hustling the car along a bit, putting some load into the system. I also admit to a preference for making my own gear changes though, if technology hasn’t already overtaken such notions, it is certainly catching up fast. The interior is everything you expect of a Jaguar - quality, good to look at, roomy, comfortable. The electric hood stows neatly under its cover which, but for our interesting climate, is where I would have it stay. For, with the windows up, the car is remarkably draught-free, and there is plenty of heat from the ventilation system. All in all, the XJS Convertible makes it too easy. But, if that is what the people want, who is Jaguar to deny them? SS 100 is an altogether more challenging proposition. I drove it only in full fresh-air mode - with the hood up, life might be a touch claustrophobic by today’s standards. There it was, sitting under a spotlight in the museum at Browns Lane. After the battery was connected, half a dozen turns of the starter motor spun the engine into life. And there we were, out on the open road. It is a very “friendly” car, and it requires that the two occupants can, at the very least, tolerate one another. For you both sit shoulder-to-shoulder. The steering is heavy by today’s standards, so the wheel is close to allow you to get your elbows out when putting in some serious effort. This is the first cause of contact. The second is in the handbrake and gearlever area. It would take the saintliest of men to avoid even the most chaste contact with a pretty girl’s right knee while changing gear or releasing the handbrake. Conveniently, the latter is to the left of the gearbox tunnel. So one has to assume that a gel knew what she was letting herself in for if she dated a young blood with an SS 100. Mechanically speaking, the gear change is also a real pleasure. The short lever’s action is precise, and you always know which gear you’re going to collect next. And a touch of double-de-clutch when changing up is simple enough to master. A cosseted modem driver can’t help feeling a touch vulnerable in a car of this vintage. We now know so much about safety facias and steering wheels that all those knobs and other protuberances seem oddly threatening. Seatbelts?! Good Lord, no. Predictably, the ride is firm. And it is bouncy - with a fair bit of pitch and quite a lot of hopping about. Perched on a small bucket seat, at 50 or 60 mph, this is all part of the fun. Of course, respect for the law - and the value of this sprightly 54-year-old - precluded further exploration of the performance envelope. But the thought of lolloping along a pre-war route nationale, at 90, or round the Brooklands banking at 125, conjures visions of real men. BACK TO BACK

BIRTH OF A LEGEND “Wait! The SS is coming,” screamed the adverts in the trade press for July, 1931. It was characteristically vivid, a hallmark-in-waiting for the publicity style of William Lyons. It was also a major gamble for Swallow Sidecars, the back-street company Lyons and his partner William Walmsley had founded in 1922 to build motorcycle sidecars in Blackpool. Still, in nine years, it had grown to providing stylish coachwork for chassis ranging from Fiat to Austin 7. The new SS caused a sensation. Low slung, it was built on a specially adapted Standard chassis. The rakish coupé and open tourer sliced through price barriers to create phenomenal interest in a society sorely tried by the financial collapses of 1926 and ‘29. By 1934 Lyons, was sufficiently confident to commission a purpose-built chassis from Standard, and have tuning-wizard Harry Weslake rework the lacklustre Standard 2.5-litre engine. The result was the first SS Jaguar, sensation of the 1935 Motor Show. Not for the last time, Lyons had plundered the ideas of other stylists, in particular the contemporary Bentley 3.5-litre by Park-Ward. However, while the Bentley cost a vast £1,100 in bare chassis form, £395 was the price of Lyons’s Jaguar. The upper-class car trade snootily dubbed the Jaguar “The Bentley of Wardour Street”, centre of Britain’s film industry, and a rich source of buyers for the car. But, while the saloon and tourer attracted public attention, the sporting world was captivated by a low, sleek roadster, which also appeared at the show. Called simply SS100, it was a thorough re-design of the previous year’s SS90. While the SS90 drew its name from its top speed, the “100” tag was slightly misleading. Even after Weslake had worked his magic, the 2.6-litre engine was hard pressed to propel the traditionally-styled sports car, with its massive headlights and Alfa Romeo-inspired wings, beyond 96 mph. A privately-entered SS100 won the RAC Rally in 1937, while a factory team took the team prize. But, on the tracks, the established competition was just too powerful. The answer lay in more power, and Lyons commissioned the 3.5-litre engine in 1937. From 1938 the SS I00 became a real winner. Lyons himself won a sports car race in an SS100 at Donington Park, and his chief engineer Tommy Wisdom lapped Brooklands at 125 mph in a development model. But the car’s real triumphs had still to come. After the war, Ian Appleyard - Lyons’s son-in-law and a Jaguar distributor - scored a string of storming class and trophy wins in the Alpine, Tulip and Monte-Carlo rallies. The car he used, LNW I00, still survives in private hands. A real aristocrat, it was progenitor of a line that was to dominate Le Mans in the 1950s and make triumphant returns in 1988 and 1990. 1,238 words Copyright © by Anthony Howard for Daily Mail Motor Review |