|

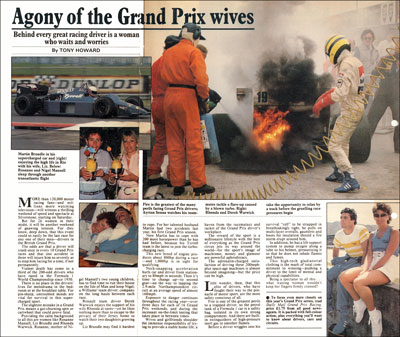

Behind every great racing driver is a woman who waits and worries MORE than 120,000 motor racing fans-and millions more watching television-will witness a thrilling weekend of speed and spectacle at Silverstone, starting on Saturday. But, for 26 women in their midst, it will be another weekend of gnawing tension. For they know, deep down, that this event could so easily be the last race for any one of their men – drivers in the British Grand Prix. The odds are that a driver will crash once in every 10 Grand Prix races and that one accident in three will injure him so severely as to stop him racing for a time, if not permanently. Violent death has come to a third of the 200-odd drivers who have raced in the Formula 1 World Championship since 1950. There is no place in the drivers’ lives for melodrama in the bedroom or at the breakfast table. For pin-sharp, untroubled minds are vital for survival in this super-charged sport. The slightest mistake in a Grand Prix means a gut-churning spin or cartwheel that could prove fatal. Providing the calm background to all this are women like Rosanne Mansell, Liz Brundle and Rhonda Warwick. Rosanne, mother of Nigel Mansell’s two young children, has to find time to run their house on the Isle of Man and keep Nigel, a Williams team driver, company on the long hauls between each race. Renault team driver Derek Warwick enjoys the support of his wife Rhonda at races – yet he likes nothing more than to escape to the privacy of their Jersey home to watch their two daughters growing up. Liz Brundle may find it hardest to cope. For her talented husband Martin had two accidents last year, his first Grand Prix season. Now Martin has to cope with 200 more horsepower than he has had before, because his Tyrrell team is the latest to join the turbo-charging race. This new breed of engine produces about 800bhp during a race – and 1,000bhp is in sight for qualifying. Neck-snapping acceleration hurls car and driver from stationary to 80mph in seconds. Then it’s time to change up – to second gear – on the way to lapping the 2.9-mile Northamptonshire circuit at an average speed of almost 160mph. Exposure to danger continues throughout the racing year – over three days for each of 16 Grand Prix weekends, and during the incessant on-the-limit testing that takes place in between times. Wives and girlfriends shoulder the immense responsibility of trying to provide a stable home life, a haven from the razzmatazz and racket of the Grand Prix driver’s workplace. The reward of the sport is a millionaire lifestyle with the best of everything as the Grand Prix circus bets its way around the world – for the sport’s image of machismo, money and glamour are powerful aphrodisiacs. The adrenalin-charged satisfaction of driving these 200mph-plus space-age machines is almost beyond imagining – but the price can be high. Little wonder, then, that this elite of drivers, who have fought their way to the pinnacle of motor sport, are the most safety conscious of all. Fire is one of the greatest perils to a trapped driver, so the petrol tank of a Formula 1 car is a safety bag, isolated in its own strong compartment. And there are built-in extinguishers of high-pressure inert gas to smother flames. Before a driver wriggles into his survival ‘cell’ to be strapped in breathtakingly tight, he pulls on multi-layer overalls, gauntlets and boots for insulation should a fire storm erupt around him. In addition, he has a life-support system to pump oxygen along a tube to his helmet, pressurizing it so that he does not inhale flames and fumes. This high-tech gladiatorial clothing is the mark of total commitment to winning – pushing a driver to the limit of his mental and physical capabilities. Being a spectator to all this, what waiting woman wouldn’t keep her fingers firmly crossed? 653 words copyright © by Anthony Howard for Weekend |